Setting the Stage

The early 20th century Catholic miracle known as “Our Lady of Fatima” is one of the most famous miracles of the modern era- and certainly the most beloved among Catholics.

recently joined Substack to publish an extremely detailed article making the case that this miracle is legitimate. He believes that his argument is “rigorous enough to persuade those that are strongly predisposed towards skepticism,” that the “best explanation is that Fatima was divine vindication of Catholicism,” and that “skeptical explanations… are not tenable.” His arguments, while methodical and clear, are not necessarily new- nor do they claim to be. He leans heavily on a 2021 paper put out by the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome.Skyrocketing to hundreds of subscribers in a matter of days, with hundreds of likes and comments, the post has quickly become topical in the Substack philosophy-adjacent community.

The default response from skeptics was broadly the same as it is to basically all alleged supernatural activity: that is to say, dismissive. Perhaps fairly (but, perhaps not, as we are about to investigate), Ethan challenged these skeptics to engage with his argument and keep the debate strictly to the evidence for or against.

So, in response,

just published his own extremely detailed investigation into Ethan’s claims. It’s a beautiful piece of skepticism. Rather than dismiss offhand the claims that many skeptics instinctively find silly, he spent 18 hours of his life engaging every point thoughtfully, thoroughly citing his sources (humorously, often the same as Ethan’s), presenting in every case the plausible naturalist explanation, and ending with this absolute banger of a conclusion:The Marian Apparitions are in ribbons — there is zero compelling reason for a person with a skeptical outlook to believe in divine intervention in any part of that story, or in any story Muse tells in the future that resembles it. What is left then? An excitable crowd — whose core, critical mass was tens of thousands of devout pilgrims — saw something cool in the sky when it was told to look for it. The clouds seem to have parted at an opportune time to facilitate this. Fine, let’s stipulate that. Now we’re all supposed to take communion?

Skeptics should not be convinced by Muse’s arguments.

And they aren’t.

Lazy Skepticism

Now, Evan has clearly put in the work to justify coming away with his skeptical conclusion. But many skeptics, myself included, found the original post so unconvincing that it wasn’t worth putting in the work to refute. And, while we welcomed Evan’s analysis as entertaining and fascinating, we didn’t actually need it to feel confident in our initial rejection of the claims.

But a neutral observer might reasonably question this. Afterall, how can you claim to be unbiased while dismissing Ethan’s claims without even engaging with his evidence?

The problem is that the class of claims to which Ethan’s belongs to, the supernatural, is an extremely poor one. Every day there’s a new alleged miracle, UFO sighting, conspiracy theory, and ALL of these people are 100% convinced they are right and are happy to drag you down into the weeds to debate their ‘evidence.’ The miracles never stop. Ethan’s Lady of Fatima post is merely “the first installment in a series of articles surveying the evidence for Catholic miracles.” Brace yourself, for there are many more on the way!

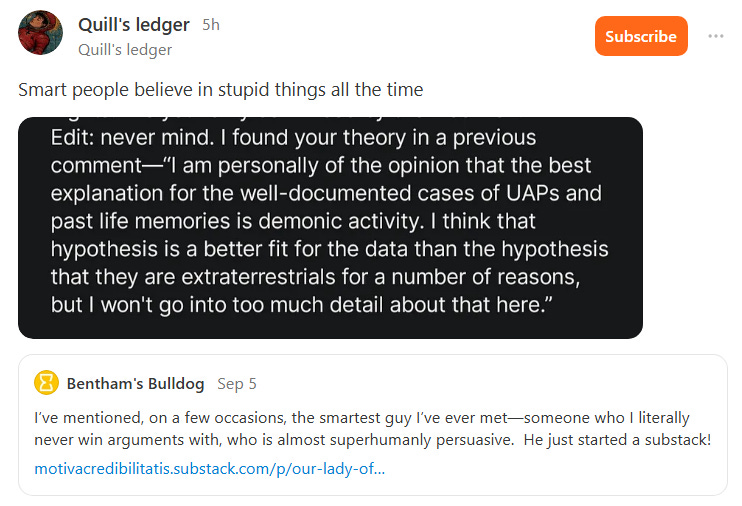

For instance,

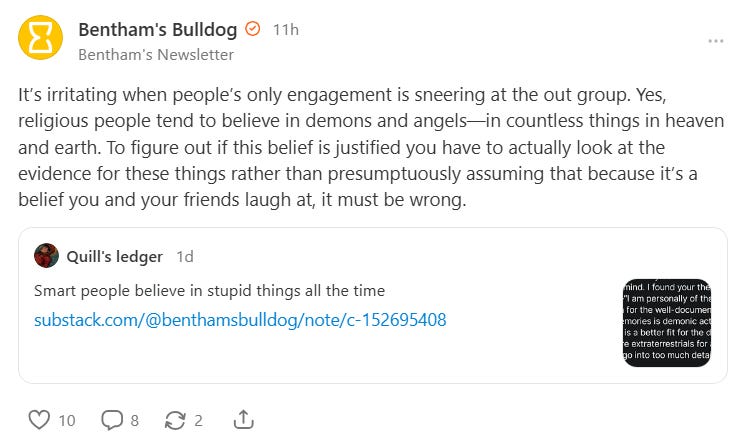

pokes some fun at a different claim from Ethan: that ‘demonic activity’ is the best explanation for UFO sightings.Not only does Ethan believe this, but apparently Bentham does too, and he’s annoyed that Quill’s response is “sneering“ rather than “actually looking at the evidence.”

So, our champion impartial skeptic Evan, who spent 18 hours researching and debunking Ethan’s last miracle claim, will now need to do the same thing for demonic activity causing UFO sightings!

The fundamental problem is that there are so many reasons to be skeptical of all miracles, not specifically Fatima or demons. As Carl Sagan famously said, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” And miracles are among the most extraordinary claims in existence.

The Problem with Miracles

1) Natural Law

David Hume famously argued that miracles, defined as violations of natural law, can never be rationally believed on testimony alone. Since the laws of nature are established by consistent, universal experience, the probability of them being suspended is always lower than the probability that a witness is mistaken, deceived, or exaggerating. In his framework, no report could ever outweigh the cumulative evidence for the regularity of nature. Hume’s maxim, that “a wise man proportions his belief to the evidence,” still forms the backbone of modern skepticism: it is always more likely that human testimony errs than that the fundamental order of the universe is broken.1

Note that if one already believes in Catholicism, then a strong confirmation bias makes it much easier to accept the idea of natural laws being broken.

has highlighted this in several places. There’s a great irony in attacking any and all naturalist explanations as ‘implausible’ while simultaneously arguing for extremely specific religious beliefs that any neutral observer would find at least as implausible.2) Selectivity

A persistent critique of miracles is their apparent arbitrariness. If an all-loving and all-powerful God acts through miracles, why do they occur in limited, almost capricious ways? Why heal one pilgrim’s illness while leaving millions to suffer, or appear to small villages but not to the wider world? Such selectivity undermines the idea of divine justice. Miracles look less like universal signs of God’s care and more like isolated anomalies that raise troubling questions about why countless equally needy people receive no intervention at all.2

3) Divine Hiddenness

Philosophers have long pressed the “hiddenness” problem: if God genuinely desires relationship with all people, why reveal himself through obscure, disputable, and culturally bound miracles instead of through clear, universal evidence? Miracles often occur in ambiguous settings, relying on subjective interpretation and prone to naturalistic explanation. If you care to reveal yourself, why not do so with clarity? If you don’t care to reveal yourself, why are there any miracles at all?3

4) Religious Pluralism

One of the sharpest critiques is that miracles are claimed across many traditions. Catholics point to Lourdes, Muslims recount the splitting of the moon, Hindus cite the milk-drinking statues, and Buddhists report relic miracles. Even the non-religious report UFOs, Bigfoot, and the Lochness monster. If miracles are supposed to authenticate a specific faith, the fact that they appear in competing religions undermines their value as evidence.4

You either have to believe that 1) many miracles are true, supporting many religions, 2) every single miracle ever reported is false except for specifically the miracles of your own religion, even though the same criticisms can be levied against all of them, or 3) miracles are cultural, not divine.

People like Ethan are in camp 2. But as Richard Dawkins famously pointed out, this is more than a bit weird: “We are all atheists about most of the gods that humanity has ever believed in. Some of us just go one god further.”

5) Mass Suggestion

Psychological research shows that large groups can share powerful illusions under conditions of expectation, stress, or excitement. From UFO flaps to phantom airship panics, crowds have often testified with confidence to phenomena that later had mundane explanations. Many miracles fit this pattern: thousands reporting dazzling visions or strange lights that prove to be atmospheric or optical effects. Mass suggestion offers a natural and repeatable mechanism that can account for the scale and uniformity of miracle reports without invoking supernatural intervention.5

6) Unreliable Testimony

There’s a reason that eyewitness testimony is no longer considered reliable in courts: it is notoriously fallible. Memory is not a static recording, but a reconstructive process easily shaped by later discussion, retelling, and bias. Studies show that eyewitness accounts frequently diverge and grow more detailed with time, even in ordinary events. When miracle stories are passed along by believers, edited by institutions, and retold across decades, the testimony becomes even less reliable. To base belief in supernatural suspensions of nature on such fragile evidence is philosophically untenable- as Hume argued.6

7) Stress Response: Search for Meaning

Miracle reports often surge in times of crisis (war, plague, political unrest) when communities are desperate for signs of hope. Psychology suggests that under acute stress, people interpret ambiguous events as meaningful, perceiving divine reassurance in natural anomalies. This “meaning making” desire explains why miracles appear most where they are most needed emotionally, not where evidence is most objective. Far from proving supernatural action, miracles merely reveal the human drive to find order and comfort amidst chaos.7

8) Confirmation Bias (and Authority Influence)

Belief in miracles is also sustained by cognitive biases. People tend to notice and remember evidence that fits their preexisting worldview, while disregarding disconfirming data. And then when a religious authority declares an event miraculous, that interpretation gains legitimacy and spreads quickly, reinforcing group identity. Even neutral observers can be swept up in the consensus of those around them. This convergence creates the illusion of independent corroboration when, in reality, testimony is shaped by expectation and authority, not by dispassionate evidence.8

Conclusion

It’s not that the evidence for Our Lady of Fatima is specifically poor. In fact, after reading both Ethan’s original post and Evan’s response, I’m inclined to say that Our Lady of Fatima might be one of the most compelling miracles I’ve heard about.

But that’s like saying of all the neighborhood squirrels, my favorite one is the most likely to reinvent algebra. It’s like calling my amazingly talented Roomba the strongest candidate to lead the AI rebellion that overthrows human civilization.

The ‘most compelling’ idea in a broader class of extremely uncompelling ones simply isn’t good enough for anyone not already looking through the lens of confirmation bias.

I enjoyed this, I just want to highlight something else that irritated me about the Muse article that you didn’t touch on. There is an unbelievable level of self-confidence in the analysis of physical phenomena. It is horribly difficult to conclude things from still images, let alone that the drying pattern of clothes at the miracle “suggests that this ‘heat ray’ had an unusually IR-rich, blue/UV-poor spectrum.”

My PhD was largely optics, so I become even more skeptical when people stray into my field. It is VERY hard to draw conclusions from bad data that stand up to close scrutiny, even when you took it yourself—one of my formative experiences as a young graduate student was nearly publishing data that was complete BS, despite matching my simulations exactly. Analyses of 100 year old photographs to infer the angular distribution of light sources? Inferring their spectra?? Insisting that no other explanations are “tenable”??? Oy.

God, I was going to write something like this, you beat me to it. I probably wouldn't have finished in time either way.