How Do We Know if it Works?

The Only Supplements Worth Taking

A Brief History

Medical research is very, very hard. The early approach was straight forward and intuitive: eat some herbs and see what happens. The famous Greek physician Galen was able to develop complex herbal remedies like this that were used for the next thousand years.1 But many of his conclusions ended up being wrong! His most famous medicine was a universal antidote called Theriac, that contained up to 70 different ingredients- nearly all of which have since been shown to be useless.2 The only ingredients that have stood the test of time are opium, honey, and a few spices like ginger. The study methods that he used simply were not sophisticated enough to isolate cause and effect and led to many erroneous conclusions.

Eventually, we realized that these simple experiments were not going to reliably lead to useful results. In the 1700s and 1800s, researchers began introducing more sophisticated controls into studies.3 They started splitting study subjects into different groups that received different treatments and used dummy pills to control for the placebo effect.

But the major breakthrough was made by Ronald Fisher in his 1935 book A Design of Experiments.4 He was analyzing crop yield data in England, and had a major problem: all the fields had inherent variability in soil, moisture, sunlight, etc. It was therefore impossible to know if a certain fertilizer was effective, or if the difference in results was due to random variation of the fields! His innovation was to reason that the treatment should show up as an improvement in the average of the fields, even if you couldn’t be sure about the effect on any specific one. And that if he first separated the fields into a large number of randomly assigned, smaller plots, he could significantly improve the accuracy of the mean measurements (law of large numbers).

The medical field quickly realized the applications, and the 1946 MRC Streptomycin Trial is recognized as the first modern randomized controlled trial in medicine.5 A relatively large number of Tuberculosis patients were randomly assigned to receive either medicine or bed rest (control group), and the radiologists evaluating X-rays were blinded as to what group the patient was in. It also used objective measurements such as survival rates and analyzed the data using modern statistical methods like confidence intervals.

Just compare how advanced this methodology is to poor Galen back in 100 AD!

Where Do We Stand Today?

Today, only randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies are considered reliable by most experts. And even these gold standard studies are plagued with many problems:

Selective reporting refers to people only publishing interesting results, as there is no incentive to publish a failed experiment. You aren’t going to win any awards or increase your funding with uninteresting conclusions, so what happens is that 100 different researchers conduct 100 similar studies and then only the 5 studies that happened to find a result (by chance) get published. This undermines the validity of published research and contributes to the reproducibility crisis.6

The generalizability of study results is also often dubious. For example, oftentimes a vitamin only demonstrates benefit to those were deficient to begin with. If there is a widespread vitamin XYZ deficiency in the population for example, then many studies will show promising results for supplementation. But it is unclear whether people without a deficiency will see any benefit.

Conflicts of interest are also common, where studies are funded by corporations looking to test their drugs. It should be obvious that in these instances, even with the best intentions, it is possible that results end up biased.

Dosage and administration method of are often important and overlooked in the media. There may be some benefit demonstrated in a controlled setting where study subjects are overseen applying a very specific dose in a specific way, but that doesn’t mean taking a pill every day at home will achieve the same results.

Case Study

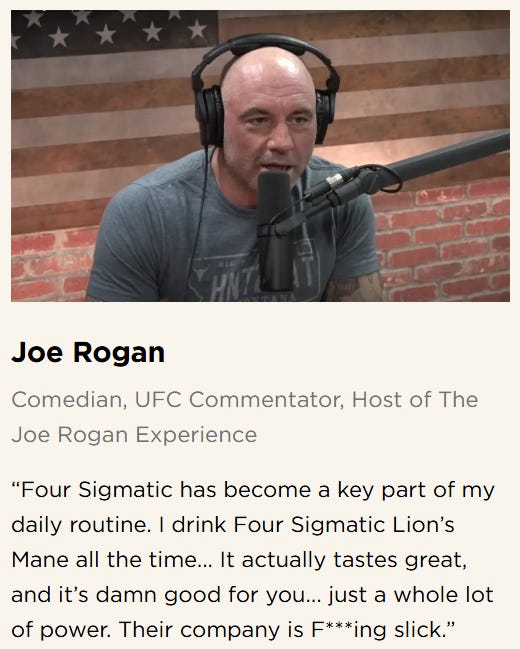

Joe Rogan recommends a lot of supplements, but one recommendation that is very consistent is Lion’s Mane mushroom. He’s so enamored with it that he has even replaced his morning coffee with a Lion’s Mane version from the brand Four Sigmatic.

This sort of thing is extremely common. You’ve probably already been pitched supplements multiple times today from influencers or on social media banners. Let’s walk through how to use ChatGPT to quickly investigate these claims.

So, I’m not too excited about this supplement for a variety of reasons:

I’m always skeptical of supplements I learn about from sponsored influencers

Bold marketing claims

Limited trials

Small sample sizes

Lack of objective results, mostly self-reporting or diagnostic questionnaires

Inconsistent formulations in studies and consumer products

Now this may seem overly harsh, as it does seem like there’s some evidence it could be beneficial. But you could say this about a massive number of supplements! The bar for “might be kinda helpful” is fairly low. Meanwhile there actually are a few supplements that have robust supporting evidence, and they typically look a lot more promising than what’s coming back for Lion’s Mane. For example, this is what we get back if we ask about Creatine.

Here the benefits are extremely well established with a wide variety of long-term and large-scale studies, while the weaknesses are fairly minor and do not change the overall conclusion.

The bottom line is that anything that consistently passes difficult tests is increasingly interesting but actually proving anything is remarkably difficult. Most of the value in understanding the history of study design comes from knowing what to dismiss, rather than what to accept.

Supplement List

Here’s a list of common supplements that have demonstrated sufficient evidence and risk/reward to be worth considering:

Creatine

The most studied supplement in the world, with demonstrated benefits in strength training as well as to lesser extent cognitive functions like memory. No health risks observed. The most common dosage is 3-5g daily

Zinc

Most convincingly demonstrated in zinc deficient individuals, but modest evidence that supplementation beyond the RDA decreases frequency and intensity of common illness as well as promotes wound healing. Some long-term health risks speculated at large dosages >50mg a day, but 20mg (roughly double the RDA) is well tolerated

Vitamin D

Strong evidence for wide ranging benefits in bone health as well as immune system. Most beneficial in individuals who are deficient, but vitamin D deficiency is extremely common. Recent research suggests that the RDA should be significantly increased from the current 600 IU to perhaps double that

Fiber

Strong evidence that fiber supplementation improves blood sugar modulation, lowers cholesterol, improves bowel function, and can support weight management. Fiber deficiency is extremely common in industrialized nations, with estimates ranging as high as 95% of Americans consuming less than the RDA. Add ~10g a day of supplemental fiber

Ashwagandha

Fairly promising as a supplement to aid sleep quality, reduce stress, and promote strength, in order of strength of evidence. Most studies use a dosage of approximately 500mg daily. No observed health risks

As expected, it’s a rather short list. Think I’m missing one? Let me know and we can repeat this case study!

how about magnesium?

Vitamin D3 is actually more a hormone than a vitamin. The dose for sick and older people should be whatever is required to have an optimal blood level of around 50-90 ng/ml, it could be 5000 iu/day or it could be 25000 iu, check blood levels always first. Cancer and Covid patients might need astronomical doses but they should be at the right bood level. No one should take vit D3 without taking vit K2 mk7 or mk4 (7 stays longer, 4 works more on the brain), as it will deposit calcium in all the wrong places, such as inside your arteries. The best form of vit D3 you get from the sun, unless having one of the aforementioned ailments, in which case definitely supplements are required